In this paper,1 I will discuss two instances of variation in the nominal morphology of Northern Vlax Romani varieties as spoken in Hungary. The discussion is conducted in an analogical framework, relying only on surface forms and their relationships, using the notion of schemata as introduced by Booij 2010 and taking it one step further. I will also make an attempt at defining the notion of a weak point as a locus of the emergence of variation. If different morphological tools are employed by different stems for the same semantic function within a strictly delimited paradigm, pattern-seeking may begin. The different patterns may result in one and the same stem employing different tools to express the same function; thus, the patterns will serve as different analogical forces that influence the extent and nature of variation. This paper focuses on variation in the strict sense, that is, phenomena involving vacillating stems.

1 The data

Romani is the only New Indo-Aryan language not spoken in India but rather in Europe, its closest relatives among other Indo-Aryan languages being Rajasthani and Gujarati. Although realistic estimates of the number of speakers are not easy to make, Bakker (2000) put their number at approximately 4.6 million in Europe at the beginning of the third millennium. The total number of the Romani people in Europe, including both speakers and non-speakers, has been estimated at anywhere between 4 and 12 million. Due to more recent migrations, Romani has also been spoken in the Americas, where the numbers are even harder to determine, but conservative estimates (cf. Matras 2005) suggest that there are upwards of 500 000 speakers, and there are probably more, as there are about 800 000 Romani people living in Brazil alone (cf. Gaspar 2012) and approximately one million in the United States (Hancock 2013). Romani monolingualism virtually does not exist; all speakers of Romani are at least bilingual.

The dialect classification still in use in current Romani linguistic literature builds upon the branches established by Miklosich (1872-80), relying mostly on contact phenomena. One of the four main dialect groups of Romani is Vlax Romani, which is, based on certain diagnostic features, further divided into a Southern and a Northern group, with the former spoken mostly in the Balkans, while the latter in Romania, Hungary, Moldova and Serbia. Some confusion is caused by the fact that the Northern Vlax group has often been referred to simply as Vlax Romani in papers written about Romani as spoken in Hungary (e.g. Erdős 1959, Vekerdi 2000).

Authentic and trustworthy corpora as such, of any variety of Romani, have not existed until very recently, and when looking into instances of synchronic variation, new and authentic data are of utmost importance. The situation in the international landscape is better now, although the small corpora of Thrace Romani-Turkish-Greek and Finnish Romani-Finnish have been collected with the aim of research into language contact, and the corpus of Russian Romani does not include the newly collected spoken data yet (Kozhanov 2016).

Therefore, we set out to collect new, authentic, up-to-date, real life Romani data in Hungary in 2015 within the framework of the project Variation in Romani Morphology (OTKA K 111961, project leader: László Kálmán).2 Based on a questionnaire specifically designed for this purpose by the author, but also recording spontaneous speech, we carried out fieldwork in several locations in Hungary, and thus far we have carried out Northern Vlax Romani interviews with 30 informants or groups of informants all over the territory of Hungary. Although the quantity of the data is not large, small corpora have actually been used effectively in the course of conducting valuable research (Adamou 2016). In the present study, we will exclusively rely on these data, occasionally referring to another fairly reliable but slightly outdated source, Vekerdi (1985). The Northern Vlax Romani varieties where the data come from include Lovari, Mašari and Drizari. Although sometimes considered as separate linguistic groups within Northern Vlax Romani (Erdős 1959, Tálos 2001), a comprehensive study on the Vlax dialects of Romani, Boretzky (2003) does not include them as separate dialects. Based on their similarity seen so far, I will consider them as one variety from a linguistic aspect, used by different, self-designated groups.

2 The notion of a weak point

In order to clarify what a weak point is,3 I will use the idea that the regularities on a particular level of linguistic description can be expressed in terms of schemata (Booij 2010, following the notion of schema, as described by Rumelhart 1980). Although related, schemata represent a more complex notion than constructions. While the latter denote a pairing of form and meaning (Goldberg 1995, Jackendoff 2008), the former, in the case of morphological schemata, contains phonological, syntactic and semantic information.4 For example, the schema for deverbal -er in English is as follows, where the symbol ↔ stands for correspondence (Booij 2010: 8).

![]()

Figure 1

Schema for deverbal -er in English

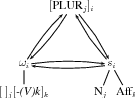

The three kinds of linguistic information included here are the phonological form ω, the syntactic information, and the semantic information. The syntactic information in the original form of the schema is encoded as N, meaning that the word containing the deverbal -er suffix is a noun. There may often be a need for morpho-syntactic properties to be specified, however (Booij 2010: 7). As the precise elaboration of the syntactic component is not part of the present paper, I will use the more general symbol S to indicate that a schema like this can represent constructions on any level of morphological or syntactic complexity. Thus, the schema for the Hungarian plural suffix -k would be the one shown in Figure 2.

![]()

Figure 2

Schema for the Hungarian plural suffix -k

Instead of this linear representation, based on the idea of Booij (2010), I suggest a circular representation of the schema, as sketched in Figure 3, where every kind of information is connected to the other two through correspondences, marked by arrows in both directions, as there is also a relationship between the semantic and the phonological information. This is not unlike what Jackendoff (2012) suggests, for example, when he claims that a word like cow is stored in memory, and “it involves a pronunciation linked with a meaning and the syntactic feature Noun” (Jackendoff 2012: 176). One reason why it is important to postulate interrelations among all three components is, as it is pointed out by Jackendoff (2012), that there are words which lack one of the components, like ouch, which has phonology and meaning but lacks syntactic features. Another reason for postulating a direct relationship between the phonological and the semantic components is that it is a significant one in the argumentation below as the variation seen in the nominal morphology of Northern Vlax Romani takes place along the correspondence between these two components, while leaving the syntactic component intact, which provides evidence for the solution proposed here, a schema showing an interrelated matrix of the three components.

Figure 3

Improved schema for the Hungarian plural suffix -k

A schema like this becomes weaker when there is a disturbance in any of the correspondences. For example, if a new phonological form, ω'i started to appear in the same syntactic position and with the same meaning as the deverbal -er or the plural -k, then this would weaken the schema, which may in turn trigger variation and the schema would become a weak point. It is also possible that more than one correspondence becomes unstable, like the locative case in Northern Vlax Romani, where the semantic component may pair up with a different phonological form and a different syntactic position, resulting in variation.5 Thus, a weak point in morphology is a schema where at least one of the correspondences is not mutually unambiguous.

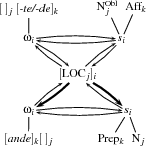

We can draw up the following, combined schema, shown in Figure 4, consisting of two schemata, for the locative case in Northern Vlax Romani. The upper section of the schema describes the agglutinative case marking: for example, e kheréste ‘in the house’. It contains the phonological form; the morpho-syntactic information, which says that the case affix is attached to the oblique base of the noun; and the semantic component, which is the locative function in this case. There is an alternative way of expressing the locative, by means of a preposition, shown in the lower section of the schema: andó kher ‘in the house’.6

Figure 4

Schema for the locative case in Northern Vlax Romani

The thick arrows in this schema mean that the correspondences in that direction prevail in the expression of the locative case, so the prepositional form is more typical than the agglutinative one. However, the presence of both forms suggests that the locative function does not exclusively correspond to either the form represented by agglutinative case marking or the form represented by the preposition.

As another example, let us take the English past tense. There is a strong relationship between the semantic function “past tense” and the way of marking commonly called “regular” (the addition of the suffix -ed). If all English verbs inflected that way, there would only be one single schema for the past tense.

However, this is not the case. There are several alternative, so-called “irregular” verbs of lower or higher frequency, making up smaller or bigger groups (sing-sang, cut-cut, keep-kept etc.). The existence of these groups of verbs means that the correspondence between the past tense function and the marker -ed is not unambiguous, and neither is the correspondence between the past tense function and the morpho-syntactic property of affixation for the past tense. Several other morpho-syntactic ways and phonological forms are used in the formation of the English past tense, for example ablaut (sing-sang), vowel shortening (keep-kept) or reverse umlaut (think-thought).

Figure 5

Schema for the English past tense

With so many schemata coalescing around the same semantic component, the correspondences become ambiguous and represent a weak point, where variation may emerge, although it does not necessarily do so. This probably depends on other factors, such as frequency, the extent of the embedded nature of the forms etc. However, if variation emerges, then we have every reason to think that there are patterns which are competing for the same function, or patterns which have some other kind of phonological or morpho-syntactic influence on the forms that begin to vary.

3 An overview of the weak points under discussion in Northern Vlax Romani

I will briefly introduce the two weak points in the nominal inflection of Northern Vlax Romani where variation occurs7 and where the surface forms (surface similarities and differences; in general, cf. e.g. Kálmán, Rebrus & Törkenczy 2012) and analogical effects might play a role in producing and maintaining this variation.

1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word hī́ro ‘a piece of news’ are h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word hī́ro ‘a piece of news’ are hīrós- and h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word hī́ro ‘a piece of news’ are h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word h1. The first weak point we will look at is the masculine oblique base. One oblique marker for masculine nouns is -es- in the singular and -en- in the plural, so the oblique bases of a word like šēró ‘head’ are šērés- and šērén-, respectively. However, this schema does not exclusively prevail within the masculine nouns. It is weakened by the existence of another phonological form, containing -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural, so, for example, the oblique forms of the word hī́ro ‘a piece of news’ are hīrós- and hīrón-, respectively.

2. The second weak point can be found in the feminine plural oblique base. The oblique marker in the singular is invariably -a-: šej ‘girl’ ~ šejá-, žuv ‘louse’ ~ žuvá-. However, there are two available patterns in the plural. One of the possible feminine plural oblique markers is -an-, for example the plural oblique base of šej ‘girl’ is šeján-; but there is also another phonological form of the feminine plural oblique marker, -en-, see for example žuv ‘louse’, whose plural oblique base is žuvén-.

4 The masculine oblique base

In this section, we will look at the first weak point, the masculine oblique base, in more detail. Following the description of the phenomenon in question, we will analyse two possible reasons for the weakness and the ensuing variation, and discuss to what extent there can be interaction between the possible reasons and the variation. They are the following.

1. The position of stress. At first glance, it seems that there is at least some sort of correlation between the variation of the oblique forms and the fact that Northern Vlax Romani lacks a straightforward stress pattern. Stress itself seems to vary, especially in words with three syllables. While the stress pattern of disyllabic words (word-initial or word-final) seems to determine the form of the oblique base unambiguously, the varying stress pattern of trisyllabic words pairs up with the unpredictability of oblique forms.

2. The number of syllables. This is related to the position of stress to some degree, as oblique forms begin to vary when the number of syllables reaches or exceeds three. The variation is especially ostensible on trisyllabic words with a stem-final /o/, while disyllabic words never vary.

4. 1 Description of the phenomenon

In this section, we will introduce the variation in the masculine oblique base and we will also see that this variation is closely linked to the masculine nouns which have a stem-final /o/.

In Northern Vlax Romani, there are two sets of suffixes for the oblique base. One of them comprises -es- for the singular and -en- for the plural, but there are masculine nouns which, without any apparent phonological or morpho-phonological reason, take a different oblique marker: -os- in the singular and -on- in the plural.

(1)šēró ‘head’ → obl. šērés-/šērén-

hhī́ro ‘a piece of news’ → obl. hhhī́ro ‘a piece of news’ → obl. hīrós-/hhhī́ro ‘a piece of news’ → obl. hhhī́ro ‘a piece of news’ → obl. hīrós-/hīrón-

Masculine nouns can be divided into three groups according to the oblique form: in the first group, only the oblique in -es-/-en- is used, in the second group, only the the oblique in -os-/-on-, and there is a third group where the two possible forms vary. The two competing patterns can be seen here next to each other throughout the whole paradigm in Table 1.

|

masculine |

bakró ‘sheep’ |

sókro ‘father-in-law’ |

||

|

singular |

plural |

singular |

plural |

|

|

Nominative |

bakró |

bakré |

sókro |

sokrurá |

|

Accusative |

bakrés |

bakrén |

sokrós |

sokrón |

|

Dative |

bakréske |

bakrénge |

sokróske |

sokrónge |

|

Locative |

bakréste |

bakrénde |

sokróste |

sokrónde |

|

Ablative |

bakréstar |

bakréndar |

sokróstar |

sokróndar |

|

Instrumental |

bakrésa |

bakrénca |

sokrósa |

sokrónca |

|

Genitive |

bakrésk- |

bakréng- |

sokrósk- |

sokróng- |

|

Vocative |

bákra |

bakrále |

sókra |

sokrále |

Table 1

The two masculine paradigms

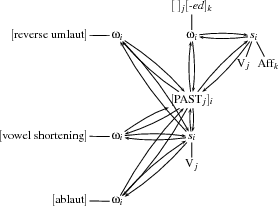

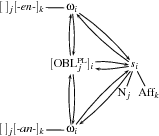

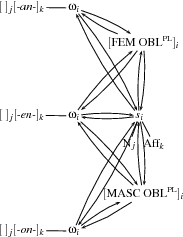

We can draw up the following schema, shown in Figure 6, for the masculine oblique base, where N is a masculine noun. It contains the oblique marker -es-/-en- as the phonological form on the one hand, and the oblique marker -os-/-on- on the other.

Figure 6

Schema for the masculine oblique base8

In this combination of two separate schemata, one containing the phonological form ωi[ ]j[es/en]k and the other one containing the phonological form ωi[ ]j[os/on]k, the same semantic content corresponds to two different phonological forms. The correspondence between the phonological form ωi[ ]j[es/en]k and the semantic content OBLj is weakened by the presence of the other schema, where the same semantic content corresponds to a different phonological form, ωi[ ]j[os/on]k, and this is also true the other way round: the correspondences between each phonological form and the semantic content OBLj are weakened by each other.

To illustrate this, the masculine nouns we have from the newly collected data are listed in Tables 2-4. Only items which have at least one attested oblique form were taken into consideration. The tables contain 28 masculine nouns whose oblique form is -es-/-en-, 23 masculine nouns whose oblique form is -os-/-on-, and, in addition, there are nine lexical items whose oblique forms vary. In the tables, the words are grouped together in the order of the number of syllables (nouns with one syllable only appear among the ones with the oblique form -es-/-en-, while nouns with four syllables only appear among the ones with the oblique form -os-/-on-). Within the groups, the words are listed according to the end of the stem: whether there is a consonant, an /i/ or an /o/.

|

noun |

attested oblique forms |

|

one syllable |

|

|

berš ‘year’ |

beršésko |

|

del ‘god’ |

devléske/dēvléske |

|

gad ‘shirt, clothes’ |

gādénca/gadéske/gādéske/gādénge/gādéngo |

|

gav ‘village’ |

gavéske |

|

grast ‘horse’ |

grastéske/grastén |

|

kašt ‘tree’ |

kaštéske/kaštésa/kašténge/kašténca |

|

kher ‘house’ |

kheréske/kherésko |

|

kraj ‘king’ |

krajéske/krajénge |

|

murš ‘man’ |

muršéske |

|

nāj ‘finger’ |

nājénca |

|

rom ‘Romani man’ |

roméske/roménca/romén/romés |

|

than ‘place’ |

thanéste/thanés |

|

vast ‘hand’ |

vastésa |

|

two syllables |

|

|

abáv ‘wedding’ |

abavéske |

|

bijáv ‘wedding’ |

bijavéske |

|

gurúv ‘bull’ |

guruvén |

|

kotór ‘cloth’ |

kotorésa |

|

manúš ‘man’ |

manušés/manušén/manušéste/manušésko/manušéstar/manušénca/manušénge |

|

bāló ‘pig’ |

bālén |

|

gāžó ‘non-Romani man’ |

gāžéske/gāžéstar/gāžén |

|

kurkó ‘week’ |

kurkéstar |

|

šāvó ‘boy’ |

šāvéske/šāvés/šāvén/šāvénge/šāvénca |

|

three syllables |

|

|

gēzešésa |

|

|

koldúši ‘beggar’ |

koldušéstar/koldušés/koldušén/koldušénca |

|

kopāčéske |

|

|

pohārénca |

|

Table 2

Masculine nouns with the oblique form -es-/-en-

|

noun |

attested oblique forms |

|

two syllables |

|

|

ā́tko ‘curse’ |

ātkónca |

|

búso ‘bus’ |

busósa |

|

čāsóngo |

|

|

fōróske |

|

|

gíndo ‘problem’ |

gindóstar/gindónca |

|

hīróstar |

|

|

nāsósko |

|

|

nīpósa/nīpós |

|

|

pújo ‘chicken’ |

pujón |

|

ritóske |

|

|

trájo ‘life’ |

trajósko |

|

three syllables |

|

|

āláto ‘animal’ |

ālatón/ālatós |

|

bārōvóske |

|

|

čalā́do ‘family’ |

čalādós/čalādósa/čalādón |

|

falató ‘a little bit of food’ |

falatóske/falatón |

|

xāmásko ‘food’ |

xāmaskós |

|

jōsāgós |

|

|

laptópo ‘laptop’ |

laptopósa |

|

somsēdósko/somsēdóski/somsīdós/somsēdós/somsēdóske |

|

|

vonáto ‘train’ |

vonatósa |

|

four or more syllables |

|

|

ternimātós/ternimātóske/ternimātónca/ternimātónge |

|

|

šegīččēgóske/šegīččēgós |

|

|

sāmītōgēpósa |

|

Table 3

Masculine nouns with the oblique form -os-/-on-

|

noun |

attested oblique forms |

|

two syllables |

|

|

sókro ‘father-in-law’ |

sokróske/sokrónge/sokrénge |

|

three syllables |

|

|

bašadó ‘telephone, mobile’ |

bašadésa/bašadósa |

|

čókano ‘hammer’ |

čokanésko/čokanósko |

|

dúhano ‘tobacco’ |

duhanés/duhanéski/duhanós/duhanóski |

|

kirā́ji ‘king’ |

kirājéske/kirājénge/kirājén/kirājón |

|

mobiló ‘mobile phone’ |

mobilésa/mobilósa |

|

pokrōcésa/pokrōcósa |

|

|

four syllables |

|

|

kirčimā́ri ‘bartender’ |

kirčimārésa/kirčimārósa/kirčimāréstar/kirčimāróstar/kirčimārénca |

|

telefóni/telefóno ‘telephone’ |

telefonésa/telefonósa |

Table 4

Masculine nouns where there is variation

As for the stems whose oblique forms vary, the variation is slight in some cases, with one or the other more dominant, but there are cases, like dúhano, where we find that the amounts of the two different oblique occurrences are basically equal.9 The overall proportion of the frequency of the stems with the oblique forms -es-/-en-, -os-/-on- and the stems where the forms vary can be seen in Table 5.

|

oblique form |

number |

percentage |

|

-es-/-en- |

28 |

47% |

|

alternating |

9 |

15% |

|

-os-/-on- |

23 |

38% |

Table 5

Number and proportion of the frequency of the stems with the oblique forms -es-/-en-, -os-/-on- and the varying stems

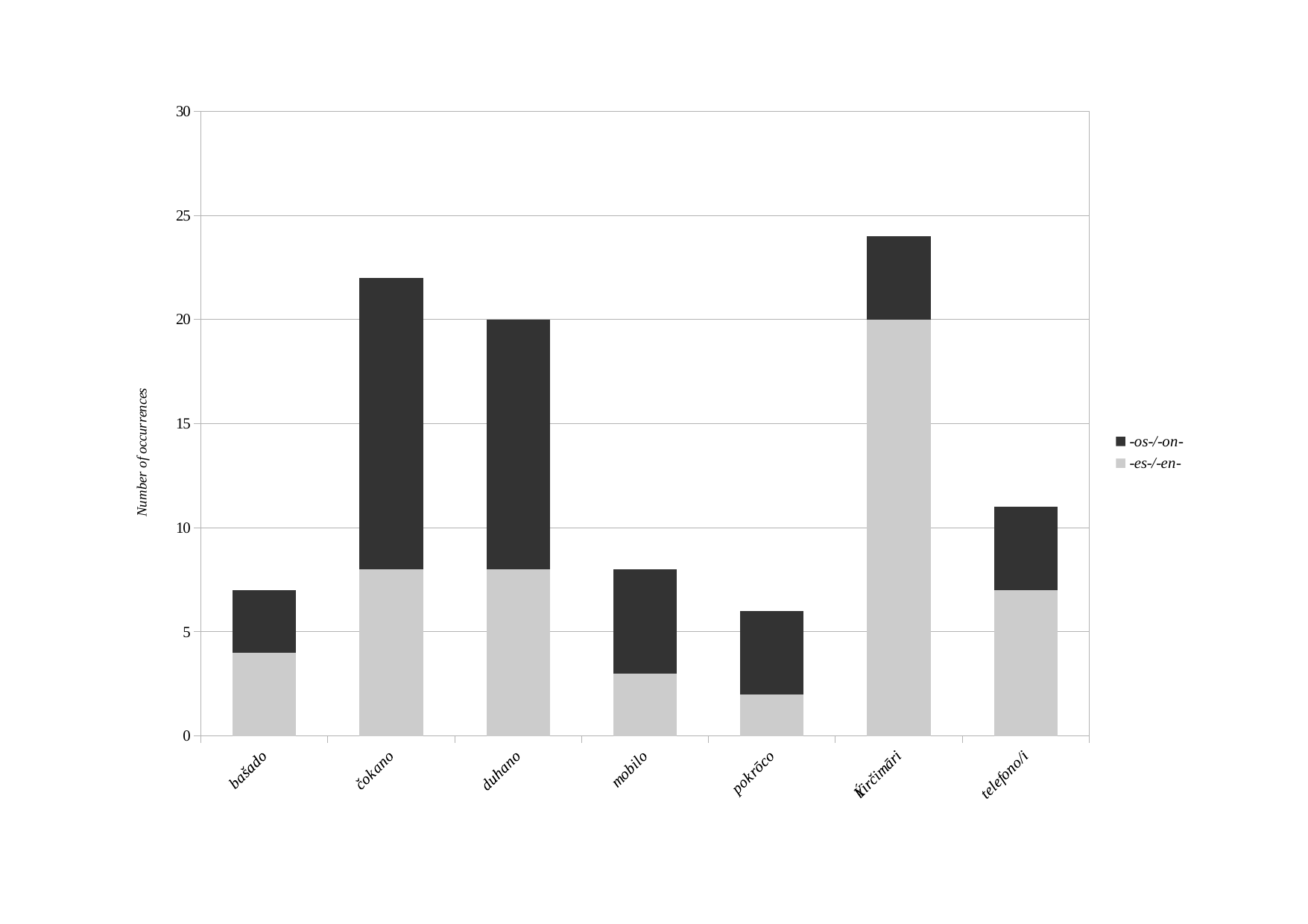

The varying stems and the total number of occurrences of both variants in the data are repeated in Figure 7, except for two items, where the variation is very slight and needs further evidence: there is only one instance containing the suffix -en- for sókro ‘father-in-law’ and there is only one instance containing the suffix -on- for kirā́ji ‘king’.

Figure 7

The total number of occurrences of the varying masculine stems in the data

Variation seems to appear more often among words where the final vowel of the nominative singular form is /o/, see for example čokáno ‘hammer’, dúhano ‘tobacco’, mobílo ‘mobile phone’, pokrVariation seems to appear more often among words where the final vowel of the nominative singular form is /o/, see for example čokáno ‘hammer’, dúhano ‘tobacco’, mobílo ‘mobile phone’, pokrṓco ‘blanket’, telefóno ‘telephone’.

The word telefóno has apparently got an alternative nominative form, telefóni, and there are some other masculine nouns ending in /i/ which show variation, like kirčimā́ri ‘bartender’, kirā́ji ‘king’. The fact that we may find variation in the oblique form of lexical items the nominative singular ending of which is -i needs further investigation and confirmation when we have more data at hand. The fact that the oblique form of the word telefóni/telefóno ‘telephone’, for example, appears both as telefonés- and as telefonós- might as well be the result of the different nominative forms. Similar instances have been attested, for example the coexistence mǖšoró and mǖšorí ‘programme’. With regard to the variation in the words kirčimā́ri ‘bartender’ and kirā́ji ‘king’ we must note that there are ambiguous cases, but there is not enough information available to draw a conclusion from them. While in the Kalderaš dialect, Boretzky (1994) documents oblique forms with -es-/-en- only for nouns with a stem-final /i/, for example limóri ‘grave’ ~ limorés-/limorén-, Cech & Heinschink (1999) only quote masculine nouns with a stem-final /i/ where the oblique suffixes are -os-/-on-, for instance juhā́si ‘shepherd’ ~ juhāsós-, doktóri ‘doctor’ doktorós- etc. The newly collected Northern Vlax Romani data from Hungary show that the situation is not so straightforward.

4.2 Possible causes and explanations

4.2.1 Variation in the position of stress

In this section, we will look at the relationship between the variation in the position of stress and the appearance of one or the other oblique form and we will see that even though one is not the direct consequence of the other (as the choice of words in Table 1, where the two different patterns are presented, intentionally suggests), there is certainly correlation between the two aspects, which means that there are certain other factors that we might want to take into consideration besides the stem-final vowel.

A possible cause of the variation in the oblique forms, which needs further investigation, is the variation in stress. Generally, and especially for disyllabic words, where the stress falls on the last syllable of the nominative singular form, there is no variation, the oblique suffix will be -es-/-en-, and where the stress falls on the first (penultimate) syllable, the oblique suffix will be -os-/-on-. No matter what the oblique ending is and where the stress falls in the nominative singular form, the stress in the oblique forms always falls on the oblique ending, so bakró ‘sheep’ will give bakrés-. On the level of the word, so on the surface, this results in penultimate stress: dative bakréske, locative bakréste, ablative bakréstar and instrumental bakrésa. A child who is acquiring Northern Vlax Romani as their mother tongue can base their assumptions concerning the oblique form on stress in case of disyllabic words.

For words with three syllables, on the other hand, stress may vary widely. While the oblique forms will always have penultimate stress, the stress of the nominative forms can fall anywhere between the first through the penultimate to the last syllable.

As we can see in Tables 2-4, the position of the stress cannot unambiguously predict the oblique form. While it is true that words with stem-final stress take the oblique forms -es-/-en- without exception, the oblique form of words where the stress shifts to a penultimate or ante-penultimate position is not so obvious. The words padlAs we can see in Tables 2-4, the position of the stress cannot unambiguously predict the oblique form. While it is true that words with stem-final stress take the oblique forms -es-/-en- without exception, the oblique form of words where the stress shifts to a penultimate or ante-penultimate position is not so obvious. The words padlṓvo ‘floor’ and rablAs we can see in Tables 2-4, the position of the stress cannot unambiguously predict the oblique form. While it is true that words with stem-final stress take the oblique forms -es-/-en- without exception, the oblique form of words where the stress shifts to a penultimate or ante-penultimate position is not so obvious. The words padlAs we can see in Tables 2-4, the position of the stress cannot unambiguously predict the oblique form. While it is true that words with stem-final stress take the oblique forms -es-/-en- without exception, the oblique form of words where the stress shifts to a penultimate or ante-penultimate position is not so obvious. The words padlṓvo ‘floor’ and rablṓvo ‘robber, highwayman’, for example, have the oblique forms padlōvés- and rablōvós-, respectively (cf. Vekerdi 1985), in spite of the fact that both have penultimate stress. As we can see from the newly collected data, the oblique form of certain stems vary, for example mobílo ‘mobile phone’ ~ mobilés-/mobilós- or dúhano ‘tobacco’ ~ duhanés-/duhanós-. The choice of pattern may further be complicated by the fact that the stress of the nominative form may even vary within one stem, for example kóčiši/kočíši ‘coachman’ (Vekerdi 1985). In sum, where stress in the nominative begins to vary (that is, in words with three or more syllables), the vowel of the oblique suffix will begin to vary, too.

4.2.2 The number of syllables

There might be a correlation between the number of the syllables a noun has and the degree of variation it shows concerning the oblique forms. This is what we will examine in this section, eventually coming to the conclusion that the higher the number of syllables are, the more likely it is that the oblique form will vary.

Monosyllabic nouns always end in a consonant and invariably take the same oblique pattern, so drom ‘road’ and dromés- ‘road’ obl. This pattern is valid for other nouns ending in a consonant that are disyllabic, so rašáj ‘priest’ and rašajés- ‘priest’ obl. The other pattern appears when two factors, namely disyllabicity and a stem-final vowel present themselves simultaneously. A stem-final vowel introduces a certain amount of disturbance in the system, because it conflicts with the initial vowel of the oblique suffix, which is straightforward for consonant-final stems. Among disyllabic stems with a stem-final /o/, however, there is no variation in the strict sense: every lexical item which has two syllables and a stem-final /o/ will choose either one or the other pattern, and the position of the stress (final or penultimate) appears to be a reliable clue in this case, as seen in Tables 2-4.

When the number of syllables rises to three, variation on the level of lexical items begins, and it is both intra- and inter-speaker variation. This means that the longer a word is, the more uncertain it gets which oblique stem it will take. As mentioned above, there is only slight variation for words longer than two syllables which end in a different vowel, like /i/: the frontness of the stem-final vowel will dominantly predict (or trigger) a front vowel in the oblique form. The back vowel /o/ of nouns with three syllables, however, will not be able to predict the oblique form unambiguously, just like disyllabic nouns ending in /o/ cannot.

Although there must be some among the trisyllabic masculine nouns with a stem-final /o/ that take -es-/-en- as their oblique (as attested in Vekerdi 1985, for example), our newly collected data do not contain them. However, they contain nine items with the oblique form -os-/-on- and four items whose oblique forms vary. This is somewhat in line with the varying stress pattern of trisyllabic nouns: the increase in the number of syllables increases the chance of variation, too. While the oblique form of disyllabic nouns never varies (it is either -es-/-en- or -os-/-on-), when the number of syllables exceeds two, the oblique form does begin to vary. This is further corroborated by the two items with four syllables: kirčimā́ri ‘bartender’ and telefóni/telefóno ‘telephone’.

It should also be noted in connection with the higher number of -os-/-on- oblique forms that when variation begins, that is, at the level of trisyllabic nouns, the stem-final /o/ might tip the scales in favour of the oblique form which contains an /o/ (whereas the word kirčimā́ri ‘bartender’, with a stem-final /i/, seems to prefer the -es-/-en- forms).

4.3 Summary

In this section, we had a look at the first weak point in the morphology of Northern Vlax Romani, the masculine oblique base, in more detail. Following the description of the phenomenon in question, we went over two possible reasons for the weakness and the ensuing variation and we found the following.

1. The position of stress. We saw that the stress pattern of disyllabic words (word-initial or word-final) corresponds to the choice of the oblique marker: word-initial stress corresponds to -os-/-on-, word-final stress corresponds to -es-/-en-. Stress begins to vary in trisyllabic words, and the same lexical item can occur with different stress patterns. That is exactly where the oblique markers begin to vary, too, so the varying stress pattern pairs up with the unpredictability of oblique forms.

2. The number of syllables. We found that while the oblique forms of disyllabic nouns do not vary, the oblique forms of trisyllabic nouns with a stem-final /o/ do. Based on this, it seems that the number of syllables influences the choice of oblique forms: the higher the number of syllables is, the higher the possibility of variation is.

5 A brief sidetrack: the “inherited-borrowed dichotomy”

We must mention here that in connection with the two different patterns, many (e.g. Boretzky 1989, Bakker 1997, Matras 2002) emphasise the existence of a strict morphological split between the vocabulary inherited from Indo-Aryan (as well as words borrowed from Persian and Armenian) and the vocabulary borrowed later from Greek and other (Romanian, Serbian, Hungarian etc.) contact languages.

The curious thing in Romani is that the newly arisen classes had not remained closed and limited to their constituting, i.e. Greek, lexical stratum. On the contrary, the athematic classes have become the only ones which exhibit any degree of contact productivity. Basically all post-Greek noun loans have been integrated into the new, athematic, rather than the old, thematic, classes.10 (Elšík 2000: 17)

In the nominal inflection this would appear like this: one of the patterns (the oblique in -es-/-en-) is used to inflect inherited nouns due to historical reasons, the other pattern (the oblique in -os-/-on-), being itself borrowed from Greek (Bakker 1997), is used to inflect borrowed nouns. For example, descriptions of Lovari (Hutterer & Mészáros 1967, Cech & Heinschink 1999) go along this path, with minor differences, so even masculine nouns with a stem-final -i take the oblique in -os-/-on- (Cech & Heinschink 1999: 22), which is clearly not the case, as we saw in section 6.3. Elšík (2000) discusses the historical development of nominal paradigms in detail, and, regarding the Greek-derived word fōro ‘town’, he states that diachronically fōrós- replaced fōrés-, so that the oblique form could resemble the nominative singular. However, even in a diachronic sense, this is hard to justify, as it goes against the basic layout of the inherited inflection, where the oblique singular stem ends in -es-, no matter what the nominative ending is (for example nominative singular bāló ‘pig’ and obl. sing. bālés-).

Psycholinguistic factors might interfere in the form of the extent to which a native speaker “feels” that a certain word is borrowed or not, but this is very difficult to measure. Intuitively, one would think that, although the word dúhano is an earlier loan from Serbian than the word čókano from Romanian, the similarity of Hungarian dohány might evoke a sense of the word being less old. The fact that there is only slight hesitation concerning the oblique forms of sókro does not really justify this as the current speakers of Northern Vlax Romani in Hungary have no access to Romanian at all. If the most important factor were the inherited or borrowed nature of a word, then, without direct access to the donor language, this factor would start to become obscure and there should be more hesitation, or, alternatively, the nominal classes would remain absolutely rigid, with no variation at all.

All in all, we have to dismiss the notion of the strict inherited-borrowed dichotomy, and thus, its erosion and any ‘interaction’ (Elšík 2000: 23) between the two layers, too. The two layers do not exist as there are no two specific and unique morphological systems used for one and the other; their inflection, strictly taken, is not different. What we must see clearly is that there are two patterns existing within the masculine paradigm of nouns ending in -o, and the choice may depend on several factors, including the overall frequency of the patterns. It is also true that the predominance of -os-/-on- forms in the case of sókro, for example, can be the result of the frequency of the forms of the particular paradigm itself (token frequency applied to paradigms), like in the case of the paradigm of fṓro ‘town’, where high token frequency may be the reason for the apparent lack of variation. On the other hand, variation in the case of the oblique form of a word like čókano ‘hammer’ can be the result of its lower token frequency. Other cognitive processes might play a role, too. For example, the extent of embeddedness is difficult to measure, but it may consist of such factors as how deeply embedded the word is mentally in language use, or what other notions might come into play, like even intuitions concerning the “Gypsyness” of the word.

6 The feminine oblique plural base

In this section, we will look at the second weak point, the feminine oblique plural base, in more detail. Following the description of the phenomenon, we will examine two possible aspects that might influence the choice of the plural oblique ending for feminine nouns. The two aspects are the following.

1. The masculine oblique plural -en-. Besides -an-, the other variant of the feminine oblique plural marker is -en-. The form is identical to one of the variants of the masculine oblique plural marker. As the semantic content (oblique plural) is also identical, we would like to look into the possible analogical influence of the masculine oblique plural marker on the feminine one. As we will see, the -en- form is dominant in both the masculine and the feminine nominal paradigms, which suggests that the mutual influence exists.

2. The feminine nominative plural suffixes. We will examine whether the nominative plural endings -i and -a have any connection to the appearance of one or the other plural oblique marker. We will find that there seems to be a relationship, which is made slightly more complicated by the fact that the singular ending of the nouns with the plural ending -i is -a and that of the nouns with the plural ending -a is often -i.

6.1 Description of the phenomenon

The feminine oblique singular base has one single form: -a-, so the oblique form of šej ‘girl’ is šejá-. However, the oblique plural base has got two possible forms: one is -an-, so the oblique plural base of a word like khajnjí ‘hen’ is khajnján-, but there is another one, -en-, for instance the oblique form of rThe feminine oblique singular base has one single form: -a-, so the oblique form of šej ‘girl’ is šejá-. However, the oblique plural base has got two possible forms: one is -an-, so the oblique plural base of a word like khajnjí ‘hen’ is khajnján-, but there is another one, -en-, for instance the oblique form of rā́ca ‘duck’ is rThe feminine oblique singular base has one single form: -a-, so the oblique form of šej ‘girl’ is šejá-. However, the oblique plural base has got two possible forms: one is -an-, so the oblique plural base of a word like khajnjí ‘hen’ is khajnján-, but there is another one, -en-, for instance the oblique form of rThe feminine oblique singular base has one single form: -a-, so the oblique form of šej ‘girl’ is šejá-. However, the oblique plural base has got two possible forms: one is -an-, so the oblique plural base of a word like khajnjí ‘hen’ is khajnján-, but there is another one, -en-, for instance the oblique form of rā́ca ‘duck’ is rācén-. They occur simultaneously as the feminine oblique plural base on several points of the feminine paradigm. This suggests that we are dealing with two competing patterns again.11

Table 6 shows the two different feminine paradigms. Note that the oblique singular forms of feminine nouns are completely unaffected by variation: the singular oblique marker is invariably -a-.

|

feminine |

rā́ca ‘duck’ |

māčí ‘fly’ |

||

|

singular |

plural |

singular |

plural |

|

|

Nominative |

rā́ca |

rācí |

māčí |

māčá |

|

Accusative |

rācá |

rācén |

māčá |

māčán |

|

Dative |

rācáke |

rācénge |

māčáke |

māčánge |

|

Locative |

rācáte |

rācénde |

māčáte |

māčánde |

|

Ablative |

rācátar |

rācéndar |

māčátar |

māčándar |

|

Instrumental |

rācása |

rācénca |

māčása |

māčánca |

|

Genitive |

rācák- |

rācéng- |

māčák- |

māčáng- |

|

Vocative |

rā́ca |

rācále |

mā́ča |

māčále |

Table 6

The two different patterns in the feminine

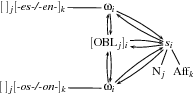

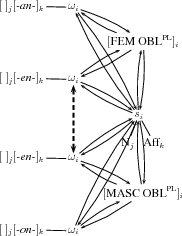

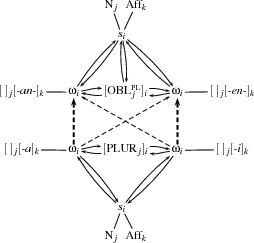

The two different patterns can be represented by the following combination of two schemata, shown in Figure 8, where N is a feminine noun. The correspondence between the phonological form ωi[ ]j[an]k and the semantic content OBL PLURj is weakened by the presence of the other schema, where the same semantic content corresponds to a different phonological form, ωi[ ]j[en]k. We can also look at it from the other direction: the correspondence between the phonological form ωi[ ]j[en]k and the semantic content OBL PLURj is weakened by the presence of the other schema, where the same semantic content corresponds to a different phonological form, ωi[ ]j[an]k.

Figure 8

The combination of two schemata for the feminine oblique plural

The feminine nouns from the newly collected data can be seen in Table 7. The items are grouped together according to their oblique plural form; items with no attested plural oblique form were excluded. Out of the total twenty items, there are four whose oblique plural marker is -an-, there are seven items whose oblique plural marker is -en-, and there are nine stems where the oblique forms vary. A striking fact here is that the number of stems where there is variation is much higher than expected based on earlier sources, like Vekerdi (1985).

|

noun |

attested oblique forms |

|

nouns with the oblique plural -an- |

|

|

xajíng ‘well’ |

xajingánge/xajingángo |

|

khajnjí ‘hen’ |

khajnján |

|

pīrí ‘saucepan’ |

pīránge |

|

māčí ‘fly’ |

māčánca |

|

nouns with the oblique plural -en- |

|

|

angrustí ‘ring’ |

angrusténdar |

|

armajá ‘curse’ |

armajénca |

|

cincārénca |

|

|

kangrí/krangí ‘branch’ |

kangrénca/krangénca |

|

kúrva ‘whore’ |

kurvéngo |

|

mesají ‘table’ |

mesajéndar |

|

rācén |

|

|

nouns with variation |

|

|

katt ‘a pair of scissors’ |

kattjánca/kattjénca |

|

māj ‘meadow’ |

māján/mājánge/mājénge |

|

papín ‘goose’ |

papinján/papinjén |

|

patrí ‘leaf’ |

patrénca/patránca |

|

šūrí ‘knife’ |

šūránca/šūrénca |

|

tjīrí ‘ant’ |

tjīránca/tjīrénca |

|

bāj ‘sleeve’ |

bājánca/bājénca |

|

bār ‘garden’ |

bāránge/bārán/bārénge |

|

bórotva ‘razor’ |

borotvénca/borotvánca |

Table 7

Feminine nouns and their oblique forms from the newly collected data

The overall proportion of the frequency of the stems belonging to the two feminine oblique plural patterns and the stems where the oblique forms vary can be seen in Table 8. We can see that the feminine class of nouns is even more affected by variation than the masculine class, with a higher percentage of all the attested stems showing variation.

|

oblique form |

number |

percentage |

|

-en- |

7 |

35% |

|

alternating |

9 |

45% |

|

-an- |

4 |

20% |

Table 8

Number and proportion of the stems belonging to the two feminine oblique plural patterns and the varying stems

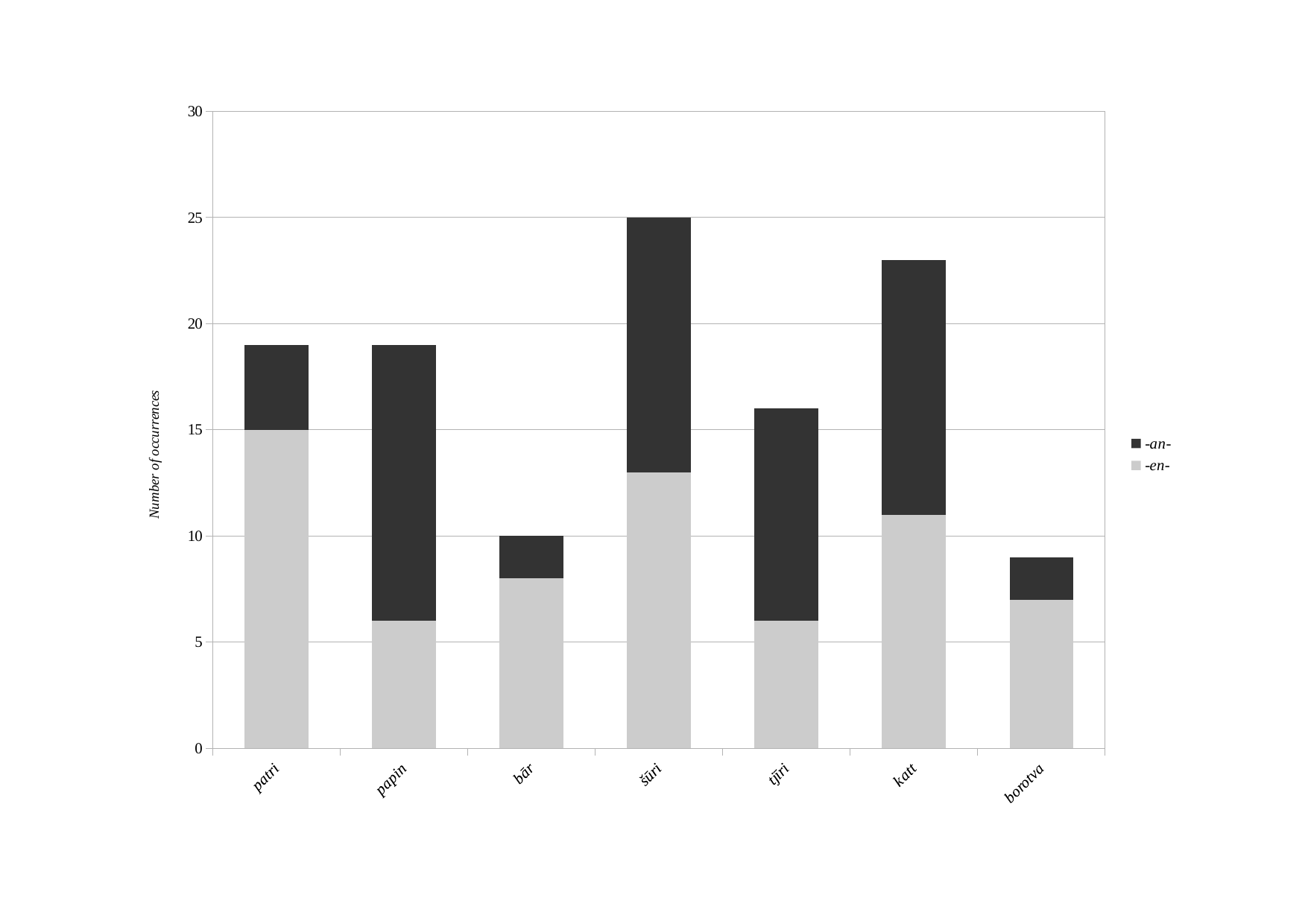

The varying stems and the total number of occurrences of both variants in the data are repeated in Figure 9, except for two items, where the variation is very slight and needs further evidence: there is only one instance containing the suffix -an- for bāj ‘sleeve’ and there is only one instance containing the suffix -en- for māj ‘meadow’.

Figure 9

The total number of occurrences of the varying feminine stems in the data

We have to note here that Cech & Heinschink (1999) try to explain this again with the difference between inherited and borrowed words: -an- is used with inherited words and -en- is used for borrowed words. This is, however, completely inconsistent with the data and even with the way the inherited-borrowed dichotomy in the masculine is traditionally analysed, and thus should be dismissed.

The general frequency of /a/ and /e/ in the Romani verbal and nominal suffixes can play a role in the presence and competition of the two patterns, although this is contradicted by the fact that the proportion of the two different forms varies among the different stems. As we could already see, while the vowels /u/ and /i/ appear less often in suffixes in general, and even then they are more typically used in derivation, /e/ and /a/ are quite common in the inflection of Romani, for example as the vowel component of nominal oblique markers, both feminine and masculine, and of personal concord markers on verbs.

As we can see in Table 9, the personal concord markers for consonantal verbs (with the inclusion of the /e/ which was analysed as epenthetic by Baló 2008) exclusively contain these two vowels.

|

|

1st sing. |

2nd sing. |

3rd sing. |

1st plural |

2nd plural |

3rd plural |

|

present |

-av |

-es |

-el |

-as |

-en |

-en |

|

past |

-em |

-an |

-as |

-am |

-an |

-e |

Table 9

Verbal personal concord markers

If we consider the fact that the first and second person plural forms are less frequent generally, we see that the proportion of personal concord markers containing /e/ and /a/ is 5:3, which corresponds to the tendencies we find for the distribution of the two vowels in the feminine oblique plural marker. Even if both the verbal and the oblique markers reflect a more general distribution or proportion of the vowels within the language, it is important to see that the distribution does not only present itself as different nominal classes formed with one or the other vowel, but also as stem-level variation, where one single stem can form the oblique with both markers.

The nominal oblique markers, including feminine nouns, can be -es-, -en, -a-, -an-, all containing /e/ or /a/. In addition, /o/ also appears in the variant oblique masculine forms -os- and -on-. The vowel /o/ is, however, not present elsewhere in the inflection. Considering all this, it follows that the variation in the feminine oblique plural between -en- and -an- is much more salient, with variation seen in nine stems out of 20, than the variation in the masculine oblique between -es-/-en- and -os-/-on, where the number of stems where there is variation in only nine out of 60.

It is also important to note that the variation always includes /e/ as one of the elements of varying pairs of vowels: in case of the masculine oblique, the variation is /e/ ~ /o/, whereas in the feminine oblique plural it is /e/ ~ /a/. Its presence is in line with the overall high frequency of /e/, while the fact that it frequently takes part in some kind of variation is in line with the hypothesis that /e/ could be a default vowel and thus it is less stable. Let us not forget that it is always deleted where there is a thematic vowel at the end of the stem of the verb.

6.2 Possible causes and explanations

6.2.1 The masculine oblique plural -en-

The presence of the -en- pattern in the feminine may be connected to its simultaneous presence in the masculine. While the -en- pattern exerts a neutralising effect, making all plural paradigms look identical and decreasing the extent of gender difference, the -an- pattern exerts an opposite effect, trying to maintain an intra-gender uniformity, being more similar to the singular oblique marker -a-. A possible, additional aspect of variation is the presence of /n/ in the plural oblique across the whole nominal morphology; /n/ is a common trait of both the masculine and the feminine paradigms, so variation emerges more easily.

The correlation between the masculine oblique plural -en- and the feminine oblique plural -en- is shown in Figure 10, where the schemata for the masculine oblique plural and the feminine oblique plural are connected through a thick dashed bidirectional arrow, indicating mutual influence. However, as we will see in Figure 11, separating the masculine and the feminine phonological components containing the -en- suffix is not necessary at all; just like the syntactic component, the identical phonological components can be conflated into a single one as well.

Figure 10

The relationship between the masculine and the feminine oblique plural endings

Let us have a look at the phenomenon through the examples of rakló ‘boy’ and rakljí ‘girl’, which are apparently close cognates of each other, related to Sanskrit laḍikka ‘child’, with the feminine form derived through gender assignment.

|

nominative singular |

nominative plural |

oblique singular |

oblique plural |

|

rakló |

raklé |

raklés- |

raklén- |

|

rakljí |

rakljá |

rakljá- |

raklján- |

Table 10

Correlation between the masculine and feminine paradigms

As we can see from the example in Table 10, the forms show great uniformity, while maintaining opposition and differentiation. The back vowel of the nominative singular rakló is replaced by the front vowel /e/ in all other forms, while the front vowel of rakljí is replaced by the back vowel /a/ in the other forms. The opposition of the nominative singular endings, /o/ and /i/, are swapped in the plural and in the oblique, but the front-back differentiation remains expressed. As we noted with regard to the masculine, disyllabic words always inflect the same way, having either /e/ or /o/ in the oblique ending. The word rakló belongs to the nouns which take -es-/-en-. The high degree of the similarity of the two words in the nominative singular maintains the contrast, but in case the word rakljí had forms like *rakljén- in the plural oblique, so if there were variation, it would not really be surprising to see forms such as *raklón- for the word rakló.

As stated before, the overall number of masculine nouns with the marker -es-/-en- is 28, as opposed to the 23 items with the marker -os-/-on- (not counting the stems where there is variation). If we compare this to the seven feminine nouns with the oblique plural marker -en- and the four feminine nouns with the oblique plural marker -an-, we can see that, at least concerning type frequency, the -en- form dominates in both the masculine and the feminine paradigms, and the number of stems where there is variation is equal: nine in both paradigms. The fact that there are more feminine nouns which take the -en- form suggests that the dominance of the -en- form in the masculine influences the feminine paradigm indeed. The neutralisation effect is shown in Figure 11, where the masculine oblique plural and the feminine oblique plural converge in the ending -en-, and diverge through the endings -an- and -on-.

Figure 11

Combined schema of the masculine and feminine oblique plural

6.2.3 The feminine nominative plural suffixes

It would be appealing to say that the nature of the stem-final vowel plays a role in the choice of the oblique plural: if it is /i/, the vowel of the oblique plural marker is always /e/, if it is /a/, the vowel of the oblique plural marker is always /a/. However, as we could see from the data in Table 7, this is definitely not the case. On the other hand, there might be a possible and even more obvious connection between the nominative plural and the oblique plural. As we could see in Table 6, where the two patterns are introduced, the feminine plural form ends in /a/ if the nominative is /i/, so for example pīrí ‘pot, saucepan’ ~ pīrá ‘pots, saucepans’, and it ends in /i/ if the nominative is /a/, see kúrva ‘whore’ ~ kurví ‘whores’. The oblique forms seem to correspond to the plural forms as for their backness.

(2)nominative singular pīrí → nominative plural pīrá → oblique plural pīrán-

nominative singular kúrva → nominative plural kurví → oblique plural kurvén-

If we have a closer look at the data, we find the following numbers and proportions. Out of the total 20 items, seven items follow the pattern. This means that if the nominative plural ending is /i/, they will take the oblique plural ending -en-, and if the nominative plural ending is /a/, they will take the oblique plural ending -an-, as seen in Table 11.

|

noun |

nominative plural form |

oblique plural form |

|

nouns with the oblique form -an- |

||

|

xajíng ‘well’ |

xajingá |

xajingán- |

|

khajnjí ‘hen’ |

khajnjá |

khajnján- |

|

māčí ‘fly’ |

māčá |

māčán- |

|

pīrí ‘saucepan’ |

pīrá |

pīrán- |

|

nouns with the oblique form -en- |

||

|

armajá ‘curse’ |

armají |

armajén- |

|

kúrva ‘whore’ |

kurví |

kurvén- |

|

rācí |

rācén- |

|

Table 11

Feminine nouns where the nominative plural ending corresponds to the oblique plural ending

Four items behave in the opposite way, so their nominative plural ending is /a/ alongside the oblique plural ending -en-. There are no nouns whose nominative plural ending would be /i/ alongside the oblique plural ending -an-.

|

noun |

nominative plural form |

oblique plural form |

|

cincārá |

cincārén- |

|

|

mesají ‘table’ |

mesajá |

mesajén- |

|

angrustí ‘ring’ |

angrustá |

angrustén- |

|

kangrí/krangí ‘branch’ |

kangrá/krangá |

kangrén-/krangén- |

Table 12

Feminine nouns where the nominative plural ending does not correspond to the oblique plural ending

The difference is significant, with almost twice as many items where there is correspondence in the backness.

Let us also check the tendencies among the seven stems where there is significant variation. Three of the stems where there is variation predominantly take either the nominative plural ending /a/ and the oblique plural ending -an-, or the nominative plural ending /i/ and the oblique plural ending -en-.

|

word |

occurrences |

pl. obl. -en- |

pl. obl. -an- |

|

papín ‘goose’ |

19 |

32% |

68% |

|

tjīrí ‘ant’ |

16 |

37.5% |

62.5% |

|

borótva ‘razor’ |

9 |

78% |

22% |

Table 13

Feminine nouns where there is variation with a bias towards the correspondence between the nominative plural and the oblique plural in backness

On the other hand, two of the stems with varying forms go against the tendency, with the predominant pattern being that of the combination of the nominative plural ending /a/ and the oblique plural ending -en-.

|

word |

occurrences |

pl. obl. -en- |

pl. obl. -an- |

|

patrí ‘leaf’ |

19 |

79% |

21% |

|

bār ‘garden’ |

10 |

80% |

20% |

Table 14

Feminine nouns where there is variation with a bias towards the opposition between the nominative plural and the oblique plural in backness

Finally, there are two stems where the proportion of the two patterns is virtually equal, indicating a high degree of variation.

Table 15

|

word |

occurrences |

pl. obl. -en- |

pl. obl. -an- |

|

katt ‘a pair of scissors’ |

23 |

48% |

52% |

|

šūrí ‘knife’ |

25 |

52% |

48% |

Feminine nouns where there is a considerable degree of variation with no significant bias

In sum, we can say that the nominative plural ending can definitely or predominantly predict the corresponding oblique plural for eleven stems, while this prediction goes awry in case of only seven stems. This suggests that there is a tendency for the feminine nominal plural suffix to influence the choice of the oblique plural suffix, but it might be weakened by the fact that the nominative singular suffix is exactly the other way round. This is shown in Figure 12, where the schemata for the nominative plural and the oblique plural are connected through dashed arrows. The thick arrows represent the dominant direction of prediction, while the thin arrows show a weak correlation.

Figure 12

The relationship between the feminine nominative plural and the feminine oblique plural as shown in the form of schemata

6.3 Summary

In this section, we looked at the second weak point, the feminine oblique plural base, in more detail. Following the description of the phenomenon, we examined two possible aspects that might influence the choice of the plural oblique ending for feminine nouns and we found that the two aspects seem to exert influence indeed.

1. The masculine oblique plural -en-. Besides -an-, the other variant of the feminine oblique plural marker is -en-, which is identical to one of the variants of the masculine oblique plural marker. We looked into the possible analogical influence of the masculine oblique plural marker on the feminine one. As we saw, the form -en- is indeed dominant in both the masculine and the feminine nominal paradigms, which suggests that the influence exists.

2. The feminine nominative plural suffixes. We examined whether the nominative plural endings -i and -a have any connection to the appearance of the plural oblique marker -en- and -an-. We found that there is a relationship between the nominative and the oblique plural endings, with the front vowel /i/ predominantly predicting the marker -en- and the back vowel /a/ predominantly predicting the marker -an-. We also found an overall dominance of the marker -en-.

7 General conclusion

Through the example of the variation in the nominal morphology of the Northern Vlax Romani varieties spoken in Hungary, I would like to demonstrate that variation is an essential part of language and that its study brings us closer to a better understanding of the nature of language change, as language change is often preceded by variation. The study of variation, and especially intra-dialectal and intra-speaker microvariation might also provide us with some insights into the essential cognitive processes behind the structure and use of language. Although neurolinguistics is still in its infancy, based upon recent research in the field (Menn & Duffield 2014) it seems that construction-based and usage-based approaches can provide insights into how grammars can come closer to reflecting what our brains do. This “non-analytical” approach is also in line with recent experimental research in phonetics, speech perception and speech production (Port 2007, Port 2010). Apparently, in speech perception ‘the data strongly suggest that listeners employ a rich and detailed description of words’ (Port 2007: 145) instead of abstract, segmented forms. In other words, ‘listeners encode particulars rather than generalities’ (Pisoni 1997: 10).

I have also attempted to show that the simultaneous presence of two forces, regularisation on the one hand and differentiation on the other make language a dynamic process. For the study of variation and gradience, analogy proves a useful tool, especially because even variation can be gradient. This is illustrated through the phenomena we encounter in the nominal system of Northern Vlax Romani. Within the nominal morphology, we see two distinct, internally uniform patterns for both the masculine oblique forms and the feminine oblique plural forms. On the one hand, uniformity means that we do not find mixed paradigms; on the other, uniformity also refers to what we called regularisation above: the presence of the marker -en- in the feminine plural oblique is variation in the feminine plural paradigms but uniformity in the wider category of nouns.

References

Adamou, Evangelia (2016). A Corpus-Driven Approach to Language Contact. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bakker, Peter (1997). Athematic morphology in Romani: The borrowing of a borrowing pattern. In Matras, Yaron, Peter Bakker & Hristo Kyuchukov (eds.). The Typology and Dialectology of Romani. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 1–21.

— (2001). Romani in Europe. In Extra, Guus & Durk Gorter (eds.). The Other Languages of Europe. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. 293–313.

Baló, Márton András (2008). A Strange Case of Defectiveness in the Lovari Verbal Paradigm. In László Kálmán (ed.) Papers from the Mókus Conference. Budapest: Tinta. 118–136.

Barbiers, Sjef, Leonie Cornips & Susanne van der Kleij. (eds.) (2007). Syntactic Microvariation. Amsterdam: Meertens Institute.

Booij, Geert (2007). Construction Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boretzky, Norbert (1989). Zum Interferenzverhalten des Romani (Verbreitete und ungewöhnliche Phänomene). Zeitschrift für Phonetik, Sprachwissenschaft und Kommunikationsforschung 42. 357–374.

— (1994). Romani. Grammatik des Kalderaš-Dialekts mit Texten und Glossar. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

— (2003). Die Vlach-Dialekte des Romani. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Brandner, Ellen. (2012). Syntactic Microvariation. Language and Linguistics Compass, 6: 113–130.

Cech, Petra, Christiane Fennesz-Juhasz & Moses F. Heinschink (1999). Texte österreischer Lovara I. Arbeitsbericht 2 des Projekts Kodifizierung der Romanes-Variante der österreichischen Lovara (hrsgg. von Dieter W. Halwachs). Vienna: Verein Romano Centro.

Cech, Petra & Moses F. Heinschink (1999). Basisgrammatik. Arbeitsbericht 1a des Projekts Kodifizierung der Romanes-Variante der österreichischen Lovara (hrsgg. von Dieter W. Halwachs). Vienna: Verein Romano Centro.

Elšík, Viktor (2000). Romani nominal paradigms: their structure, diversity, and development. In Elšík, Viktor & Yaron Matras (eds.) (2000). Grammatical relations in Romani: The noun phrase. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 9–30.

Erdős, Kamill (1959). A Békés megyei cigányok. Cigánydialektusok Magyarországon. Gyula: Erkel Ferenc Múzeum.

Gaspar, Lúcia. (2012). Ciganos no Brasil. Pesquisa Escolar Online. Recife: Joaquim Nabuco Foundation. Available (November 2017) at http://basilio.fundaj.gov.br/pesquisaescolar_en/index.php?option=com_content&id=1263:gypsies-in-brazil-ciganos-no-brasil.

Goldberg, Adele E. (1995). Constructions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hancock, Ian F. (2013). The Schooling of Romani Americans. An overview. In: Miskovic, Maja (ed.). Roma Education in Europe. Practices, policies and politics. New York, NY: Routledge. 87–100.

Hutterer, Miklós & György Mészáros (1967). A lovári cigány dialektus leíró nyelvtana. Budapest: Magyar Nyelvtudományi Társaság.

Jackendoff, Ray. (2006). On conceptual Semantics. Intercultural Pragmatics, 353-358.

— (2008). Construction after construction and its theoretical challenges. Language 84: 8–28.

— (2012). Language. In: Frankish, Keith & William M. Ramsey (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Cognitive Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 171-193.

Kálmán, László, Péter Rebrus & Miklós Törkenczy (2012). Possible and impossible variation in Hungarian. In Kiefer et al. (eds.) (2012). 23–49.

Kozhanov, Kirill (2016). Is there a “new infinitive” in Russian Romani? A corpus-based study of subject-verb agreement in the subjunctive. Paper presented at the Conference on Corpus-Based Approaches to the Balkan Languages and Dialects, St Petersburg, Russia.

Matras, Yaron (2002). Romani: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— (2005b). The Status of Romani in Europe. Report submitted to the Council of Europe’s Language Policy Division. Available (December 2013) at http://romani.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/downloads/1/statusofromani.pdf.

Menn, Lise & Cecily Jill Duffield (2014). Looking for a “Gold Standard” to measure language complexity: what psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics can (and cannot) offer to formal linguistics. In Frederick J. Newmeyer & Laurel B. Preston (eds.) Measuring Grammatical Complexity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 281–302.

Miklosich, Franz (1872-80). Über die Mundarten und Wanderungen der Zigeuner Europas. Vienna: Karl Gerold’s Sohn.

Pisoni, David B. (1997). Some Thoughts on "Normalization" in Speech Perception. In Keith Johnson and John W. Mullennix (eds.) Talker Variability in Speech Processing. San Diego: Academic Press. 9–32.

Rebrus, Péter & Miklós Törkenczy (2005). Uniformity and contrast in the Hungarian verbal paradigm. In Laura J. Downing, T. Alan Hall & Renate Raffelsiefen (eds.) Paradigms in Phonological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 262–295.

Port, Robert (2007). How are words stored in memory? Beyond phones and phonemes. New Ideas in Psychology 25. 143–170.

— (2010). Rich memory and distributed phonology. Language Sciences 32. 43–55.

Rebrus, Péter & Miklós Törkenczy (2011). Paradigmatic variation in Hungarian. In Tibor Laczkó & Catherine F. Ringen (eds.) Approaches to Hungarian, Volume 12: Papers from the 2009 Debrecen Conference. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 135–162.

Rumelhart, David E. (1980). Schemata: the building blocks of cognition. In Rand J. Spiro, Bertram C. Bruce & William F. Brewer (eds.) Theoretical issues in reading comprehension: perspectives from cognitive psychology, linguistics, artificial intelligence and education. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 33–58.

Tálos, Endre (2001). A cigány és a beás nyelv Magyarországon. In Katalin Kovalcsik, Anna Csongor & Zsuzsanna Bódi (eds.) Tanulmányok a cigányság társadalmi helyzete és kultúrája köréből. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem – Iskolafejlesztési Alapítvány – Oktatási Minisztérium. 317–324.

Vekerdi, József (1985). Cigány nyelvjárási népmesék. Debrecen: Kossuth Lajos Tudományegyetem.

— (2000). A Comparative Dictionary of Gypsy Dialects in Hungary. Budapest: Terebess.

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for their invaluable comments on the paper.↩

The fieldwork was carried out by Mátyás Rosenberg and the author.↩

A weak point is in fundamentally similar to an unstable point, as defined by Rebrus & Törkenczy (2011). They define an unstable point in paradigms as ‘those points in the paradigm where more than one conflicting analogical requirement applies with approximately equal strength’ (Rebrus & Törkenczy 2011: 139). Although the present paper will mainly deal with formal connections, they add that a functional relationship can also serve as an analogical connection.↩

Rebrus & Törkenczy (2005) do something similar when they underspecify the input in the framework of Optimality Theory by defining its morpho-syntactic characteristics only and rely on output-output constraints to determine the outcome of two cases of lexical allomorphy in the Hungarian verbal paradigm. The two cases are Definiteness Neutralisation and Anti-Harmony, and the constraints they use require paradigmatic uniformity on the one hand and paradigmatic contrast on the other. We may say that, in some way, the underspecified inputs correspond to the semantic and the morpho-syntactic component of the schemata, while the correspondences between the components of a schema or between components of different schemata are similar to the ranking of the constraints.↩

The variation investigated in the present paper is not completely unlike microvariation, but Sjef, Cornips & van der Kleij (2007) focus on inter-dialectal variation, using a typological or a generative approach. Further research into microvariation tries to account more “for the range and (limits) of inter- and intra-speaker variation in a principled way while at the same time testing existing formal theories against these microvariational data and thus contributing to the theory of language variation”, but it still investigates closely related language variants, thus going with a dialectologically oriented approach, “applying the formal theoretical concepts of generative grammar” (Brandner 2012: 113). However, the variation we are dealing with in Northern Vlax Romani is intra-dialectal variation, which manifests itself as either inter- or intra-speaker variation.↩

The form is in fact made up of the preposition andé and the definite article o. The article immediately precedes the noun, as seen in the agglutinative form of the locative, and inflects for case, gender and number hence the form e.↩

We must note that the present paper does not deal with the possible diachronic processes that could have led to this variation and are emphasised heavily in the literature on Romani linguistics.↩

Although the oblique case is ultimately a morphological category, it can be split up into a syntactic and a semantic component. The syntactic component Si covers the syntactic position and structure, while [OBL] denotes the semantic component in the schema. In Conceptual Semantics (cf. e.g. Jackendoff 2006), plurality, for example, is encoded as a function in the semantic structure. The oblique can also be considered as a function whose argument is the set of items being enabled to take further semantic functions on; the output of the function is the aggregate of such items.↩

More evidence for the variation comes from Cech et al. (1999), who provide a further example: the oblique form of the word kókalo ‘bone’ appears as both kokalós- and kokalés-.↩

The terms “thematic” and “athematic” are very misleadingly used instead of “inherited” and “borrowed” in papers focussing on Romani linguistics.↩

According to the literature (Matras 2002: 83, Elšík 2000: 22, Boretzky 1994: 33), the form -an- is the result of a renewal or assimilation on the basis of the oblique singular; in other words, it would be a differentiation process aiming at paradigmatic opposition. For example, the oblique plural base of a word like krangá ‘branch’ is supposed to be krangán- (Hutterer & Mészáros 1967: 49), from an original oblique plural in -en-, and this most often happens in the Vlax dialects. However, the plural oblique of krangá ‘branch’ exclusively appears as krangén- in the newly collected data. We could begin to speculate whether one or the other is the “original” form and whether, if krangén- was the original form, it could have been retrieved after an intermediary stage; whatever the case is, all this could suggest that the variation we see here might be a sign of an ongoing change.↩